It’s tempting to think that electric vehicles are relatively new inventions. However, the race to manufacture a viable electric car began not with Elon Musk and Tesla but over one hundred years ago with Oliver Fritchle and Phaeton. Beginning his career as a chemist, Fritchle became an innovative businessman and a pioneer in the world of EV engineering.[1]

Quick Links

- Fritchle’s First Forays

- “A Colossal Mistake”

- An Extraordinary EV Pioneer

- “The Most Attractive Lady’s Car Ever Offered to the Public”

- Demise of the Electric Vehicle

- An Essential Legacy

- Further Information

Fritchle’s First Forays

Born Oliver Parker Fritchle on the 15th September 1874 in Mount Hope, Ohio, Fritchle soon exhibited an aptitude for chemistry and engineering. He graduated from Ohio State University in 1896 with a Bachelor of Science in chemistry. During his time at university he became renowned for saying:

“I’d like to do something extraordinary”.

- Oliver Fritchle

After graduating, Fritchle worked as a chemical engineer at the National Steel Company. During his two years with the business, Fritchle began experimenting with storage batteries and their suitability for powering vehicles. In 1899 Fritchle moved with his wife, Blanche A. Niswander, whom he married the same year, to Colorado. Here, he worked as the chief chemist and assayer for Argo Gold Mine.

“A Colossal Mistake”

When working in the smelting industry Fritchle would make, what one of his biographers termed, “a colossal mistake”. As Argo’s chief chemist and assayer, Fritchle mistakenly attributed zero value to the radium present in rock samples. Yet radium became the foundation upon which many fortunes were built throughout the twentieth century. Fritchle's aforementioned biographer goes on to explain:

“As if to make up for this colossal mistake, Fritchle in 1902 pioneered a process for the analysis and refinement of tungsten ores that became the basis for a method applied for decades.”

- Oliver Fritchle Biographer, 'Late Great Engineers: Oliver Fritchle - EV Pioneer'

Nevertheless, 1903 saw Fritchle turn from chemistry towards automotive engineering. At the turn of the century, motorised travel captured significant public interest. At this time, 40% of US automobiles were powered by steam; 22% had combustion gasoline engines; and 38% were electrically powered. As an ex-chemist, familiar with the capabilities of storage batteries, Oliver Fritchle was interested in enhancing electric vehicles.

An Extraordinary EV Pioneer

Oliver Fritchle started by repairing electric automobiles in Denver, Colorado. He soon realised that the key to a high-performance electric vehicle was the sophistication of the rechargeable battery. Subsequently, he began to develop his own batteries. In 1903 his lead-acid battery was patented and he established O. P. Fritchle Garage Company.

Persistent in his ambition to improve automobile batteries, Fritchle's efforts resulted in a twenty-eight-cell, 400-600lb battery pack capable of powering an eight-horsepower car for approximately 100 miles (over moderately flat ground) from a single overnight charge. A phenomenal innovation. Consequently, he received his first order to build a vehicle containing this battery system in 1904. This was followed by seven orders in 1906 and twenty in 1907. Fritchle’s pride in his invention was magnified when in 1906 a car powered by one of his electric batteries won the Loretta Heights automobile climbing contest.

Despite his success, Fritchle was frustrated that car manufacturers were not keeping up with his advances. Therefore, in 1908, he set up Fritchle Automobile & Battery Company. This business would enable Fritchle to design vehicles capable of matching the performance of his batteries.

1908 also saw the birth of his second son, Stanton, who followed his brother, Oliver Eugene, born in 1905.

Free to innovate on his own terms, Oliver Fritchle and his staff devised several technological changes that would double the range of electric vehicles by halving their power consumption. Such innovations included:

- Electric braking: known today as regenerative braking, Fritchle created a new controller that would recharge the battery from a decelerating motor.

- Fritchle Milostat: this was a mounted hydrometer calibrated to display the remaining battery life as a percentage, allowing drivers to calculate the car's remaining driving distance.

- Lightweight: rather than using heavy iron frames, Fritchle used laminated ash which he explained would bend on collision and then return to its original shape.

Over the course of nine years, Fritchle Automobile & Battery Company manufactured and sold over five hundred electric vehicles including cars, trucks, and one racing car. The company offered a selection of models including the coupe, roadster, torpedo, tourer, and brougham.

Fritchle’s clientele mainly consisted of Denver’s wealthy and elite; although dealerships in Los Angeles and Salt Lake City meant his automobiles were sold in locations outside Colorado. His cars were primarily aimed at rich and notable ladies. Marketing literature pointed out the "advantages" of a Fritchle motor, such as the cleanliness of the vehicles compared to their gasoline counterparts. As such, ladies could stand close to Fritchle’s automobiles without dirtying their dresses (or so said Fritchle’s spin). Perhaps it was this marketing tactic or perhaps it was the quality of the build but in 1910, (“Unsinkable”) Molly Brown chose to purchase a Fritchle Electric. Other Fritchle Electric customers included the Denver department store Daniels & Fisher. It bought two Fritchle trucks for making deliveries.

“The Most Attractive Lady’s Car Ever Offered to the Public”

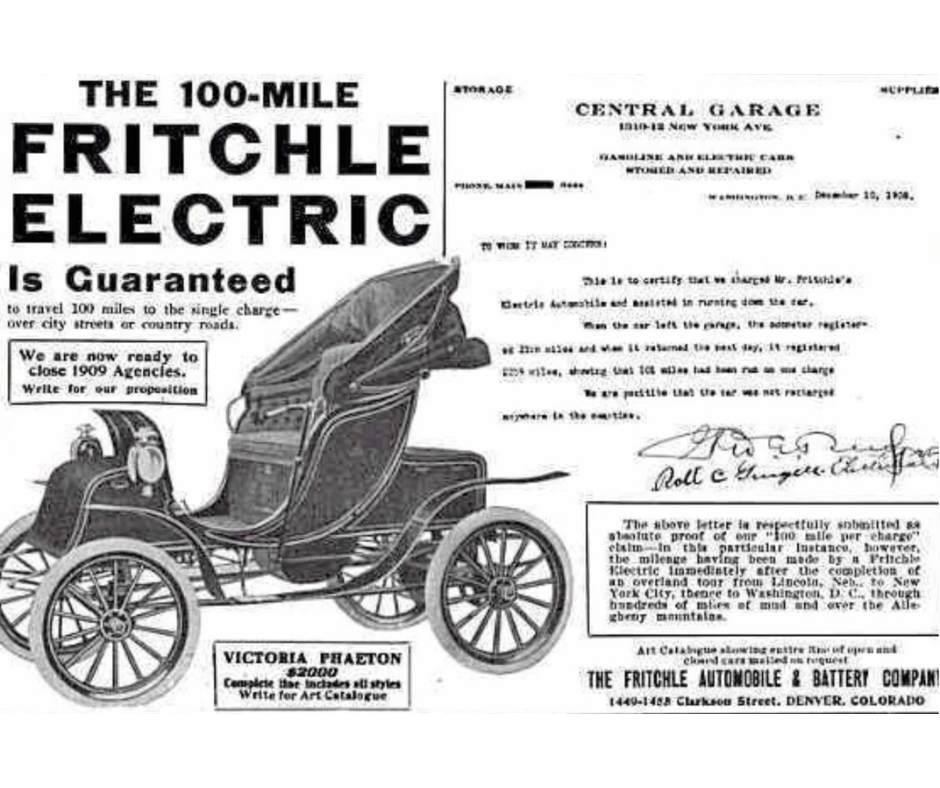

Arguably, the most famous of Fritchle’s electric cars was the Victoria Phaeton. It was touted as the:

“Ideal lady’s carriage […] [built] of the highest quality materials, workmanship and finish, calculated to give maximum satisfaction.”

- Victoria Phaeton Marketing, 'Late Great Engineers: Oliver Fritchle - EV Pioneer'

To prove the superiority of his invention, Fritchle challenged his fellow automobile manufacturers to an endurance race:

“We take pleasure in extending a general invitation to all manufacturers of electric automobiles to participate with us. We suggest that this be made a race between two points.”

- Fritchle Challenge Invitation, 'Late Great Engineers: Oliver Fritchle - EV Pioneer'

Despite nobody accepting his offer, Fritchle ploughed on with the challenge. He chose to travel in a stock Victoria Phaeton from Lincoln, Nebraska to New York City, New York. Averaging 90 miles a day, it took Fritchle approximately a month to travel the 1800 miles between the two locations: leaving Lincoln on the 31st October 1908, he arrived in Times Square on the 28th November 1908. His journey was relatively uneventful. Barring a few wrong turns, the only real misfortune occurred in Iowa. It was here that, due to a battery miscalculation, Fritchle needed to be towed for two miles to a recharging station. However, he was able to pay this kindness forward in York, Pennsylvania by towing a fossil-powered Oldsmobile for ten miles.

Whether by luck or design, it was fortunate that Oliver Fritchle encountered so few incidents. As, such was his confidence in his creation, he took very few spare parts: an additional tyre, an extra inner tube, as well as ammonia and sulfuric acid to service the batteries. His confidence was well placed. Fritchle only had to change one tyre, one fuse, and some brake linings over the entire 1800-mile endurance drive!

Demise of the Electric Vehicle

Arguably electric vehicle manufacturers in the early 1900s faced similar problems to the EV brands of today. The reason Fritchle had to market his vehicles to the elite and wealthy was that his cars were nearly three times the price of comparable gasoline models. For example, Fritchle’s Victorian Phaeton was sold at $2000 which is significantly more expensive than a Ford of the same era costing $440-550.

Furthermore, while today we are concerned about depleting fossil fuels, at the turn of the 20th century large petroleum reserves were being discovered. These findings, along with Charles Kettering’s perfection and patenting of the electrical ignition starter, provided the perfect environment for gasoline-powered vehicles to flourish. Consequently, Oliver Fritchle decided to bow out of the automobile industry. The final Fritchle Electric motors drove off the assembly line in 1917.

Ever the innovator, in the same year that Fritchle Automobile & Battery Company closed its doors, Oliver Fritchle set up a new business: Fritchle Electric Company. This enterprise focused on selling renewable wind power generation systems. It is credited with building eighty wind-electric plants in twenty American states and overseas between 1918 and 1923.

1919 saw Oliver Fritchle divorce his first wife, Blanche, to marry Hester McNutt on 26th June of the same year. In 1923, Fritchle discontinued the Fritchle Electric Company and he and his new wife moved to Chicago where he worked for Buick Motor Company. Nine years later they moved to Long Beach, California, where Fritchle worked for the Automobile Dealers Association until his retirement in 1941.

Not one to remain idle, in retirement Oliver Fritchle pursued his wide-ranging research interests, which included barnacle removal, fog dissipation, precious metals, and inventing cooking utensils! He died on the 15th August 1951 in Long Beach. He was 76 years old.

An Essential Legacy

It is difficult to characterise Oliver Fritchle as anything other than a man ahead of his time. A pioneer of clean, renewable energy he was an innovator in both the automotive and electricity industries. A forward-thinking individual, he researched and advanced alternative power sources before this discussion became mainstream and long before the world realised our urgent need for these technologies. In fact, it would be fifty years after Fritchle’s death before electric vehicles would reappear on our roads.

To meet binding 2050 Net Zero targets, in 2035 sales of new petrol and diesel cars will cease.[2] As we scramble to update our road infrastructure, while worrying about how this may change our way of living, perhaps Oliver Fritchle’s achievements might provide some comfort and inspiration. For, if he could design, develop, and manufacture a durable, dependable electric vehicle in the 1900s, then surely with our collective 21st-century knowledge and determination, we should be able to do the same.

Further Information

At PASS Ltd, we are proud to provide an array of electric vehicle charging equipment including EV charging stations, EV charging cables, and EVSE testers. Please contact a member of our Sales team on 01642 931 329 or via our online form for further help or advice.

View Electric Vehicle EVSE Testers

Browse Electric Vehicle Charging Stations

Additionally, our training centre offers a City & Guilds accredited Level 3 EVSE Charging Point Installer Course. You can find details of this course on our training website. Alternatively, contact our Training department on 01642 987 978 or via our online form for more information.

Book City & Guilds Level 3 EVSE Charging Point Installer Course

Further details regarding the regulations and requirements pertaining to the installation of electric vehicle charging points are explained in our following blogs.

IET Amendment Could Help Achieve 2035 Petrol & Diesel Ban

4 Things to Consider When Installing an EV Charge Point

Finally, for more International Men’s Day content, please click the link below.

Helping Men In Construction with Their Mental Health

[1] All the information for this blog was gathered from the following sources:

- Colorado Encyclopedia, Fritchle Electric Automobile, last accessed 17 November 2023.

- Oliver P. Fritchle Collection, Mss.01292, History Colorado, last accessed 17 November 2023.

- Nick Smith, ‘Late great engineers: Oliver Fritchle – EV Pioneer’, The Engineer, last accessed 17 November 2023.

- Wikipedia, Oliver Parker Fritchle, last accessed 17 November 2023.

Additional references are indicated in the text.

[2] Department for Transport & The Rt Hon Mark Harper MP, ‘Government sets out path to zero emission vehicles by 2025’, GOV.UK, last accessed 17 November 2023; and; Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street & The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP, ‘PM recommits UK to Net Zero by 2050 and pledges a “fairer” path to achieving target to ease the financial burden on British families’, GOV.UK, last accessed 17 November 2023.